Table of Contents

- Introduction: Why AI compliance can’t be an afterthought

- 1. Legal foundations for workplace AI in Australia

- 2. Employee consent, notice and transparency duties

- 3. Data security and governance controls for AI systems

- 4. Bias, discrimination and fairness in AI-driven work decisions

- 5. Vendor risk, data use clauses and biometric exposure

- 6. Audits, monitoring and human accountability

- 7. Practical framework to deploy compliant agentic assistants

- Conclusion and next steps

Introduction: Why AI compliance can’t be an afterthought

In many Australian workplaces, AI-driven assistants are already helping to draft performance-related communications, route customer issues, and flag employees who may be “at risk” of leaving. While the specific label “agentic prompting assistants” is still emerging, the underlying capabilities are very real. Australian HR teams are using AI tools to support performance and talent management, surfacing insights and shaping the language of feedback. Customer-facing teams rely on AI to automatically route inquiries to the right specialists and prioritise issues during peak periods. And predictive analytics platforms are being deployed to analyse workforce data and alert managers when employees show signs of being likely to leave.

These systems plan, call tools, and act across multiple platforms, often processing more data, faster and more consistently, than a human team could on its own. Who else can access it? Can you explain a decision to a regulator or court if required?

This final part of our “Agentic Prompting Assistants in the Workplace” series focuses on security, privacy, compliance and governance. It offers Australian practitioners and governance leaders a practical playbook to deploy these systems in a way that is secure, responsible, and aligned with evolving regulation, including guidance on using an Australian-hosted AI assistant designed to keep sensitive workplace data within Australian jurisdiction. While solutions like Lyfe AI are built with an onshore-first approach and use Australian-based infrastructure for data storage and processing where possible, organisations should still conduct their own due diligence and technical validation to confirm that any deployment configuration meets their specific security, data residency, and compliance requirements.

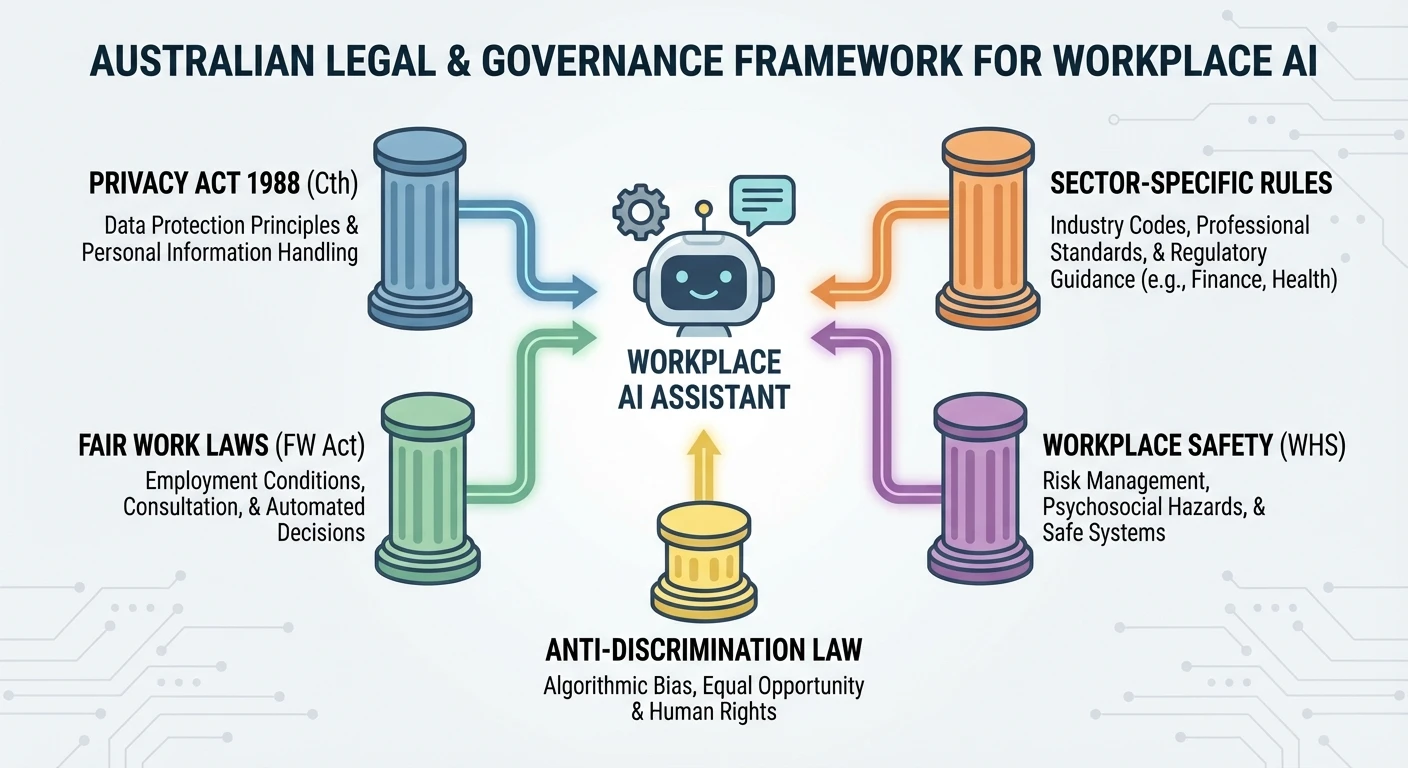

1. Legal foundations for workplace AI in Australia

Workplace AI in Australia is shaped by a mix of existing legal and regulatory frameworks, including the Privacy Act 1988 (and the Australian Privacy Principles), Fair Work and anti‑discrimination laws, workplace health and safety duties, and sector‑specific rules in areas like finance and health. These laws still apply to how you design and use AI, and should inform how you selectenterprise AI servicesand deployment partners.

From an Australian data protection perspective, the core expectations are clear: collect only the personal information that is reasonably necessary for your functions, use and disclose it only in line with defined and lawful purposes, keep it secure, and manage it in an open and transparent way with the people whose data you handle. These expectations are reflected in key Australian Privacy Principles (APPs): APP 3 limits collection to what is reasonably necessary for your functions or activities; APP 6 governs when you can use or disclose personal information, generally tying it to the primary purpose of collection (or a permitted secondary purpose); APP 11 requires reasonable steps to protect information from misuse, interference, loss, or unauthorised access; and APP 1 sets out the obligation to handle personal information in an open and transparent way, including through a clear, accessible privacy policy. When an AI system helps screen job applicants, recommend roster changes, or score employee performance, those obligations still apply because you are processing personal—and sometimes sensitive—information about people’s working lives, a point echoed in agentic AI design patterns that emphasise responsible data use.

Employment law adds another layer. If you use an AI tool to make or influence decisions about hiring, promotion, discipline, or termination, those decisions must still comply with unfair dismissal protections, adverse action rules, and discrimination prohibitions. Saying “the system recommended it” does not reduce your responsibility; it adds risk if the logic is opaque or biased. Governance teams should document when and how AI outputs are used in decision flows, and ensure there is an accessible human review stage where rights could be affected.

As regulators and courts catch up, organisations that show documented risk assessments, explicit governance roles, and clear boundaries around use cases will be better placed than those treating AI as “just another tool”, especially as more advanced foundation models enter everyday workplace tools.

2. Employee consent, notice and transparency duties

Many organisations assume that because they already hold employee data, they can freely plug it into AI tools. That assumption is risky. In Australia, employers can’t assume that existing HR data is fair game for AI projects. Under current privacy and workplace surveillance laws, using employee information for AI analytics or model training will often require a new legal basis—such as consent—or, at minimum, clear and specific notice that goes well beyond a generic reference to ‘new technologies’ in a handbook. General references to “new technologies” in a handbook are rarely sufficient, and best‑practice agentic workflow guidance emphasises early stakeholder communication. Existing privacy principles under the Privacy Act 1988 require that personal information only be used for the primary purpose for which it was collected, unless consent is obtained for a secondary purpose or that secondary use falls within the individual’s reasonable expectations. Using employee data for AI analytics or model training will often be a secondary purpose, which can trigger the need for consent—particularly where the use is novel, high‑impact, or not obviously connected to the original reason the data was collected. For sensitive information, the consent requirements are even stricter. The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) has also issued guidance on AI that emphasises transparency and fairness, reinforcing expectations around clear notice and, in many cases, consent. At the state and territory level, workplace surveillance laws frequently require employers to notify employees about monitoring activities, including certain forms of digital tracking. Recent inquiries and proposed reforms in jurisdictions such as Victoria and New South Wales are pushing for even stronger protections—like obliging employers to show that surveillance is reasonable and proportionate, and to give workers detailed advance notice about what data is collected, how it will be used, and when it will feed into AI‑driven systems. For AI‑enabled workplaces, that means privacy and surveillance obligations need to be baked into the design of any data‑hungry tools, not bolted on at the end. General references to “new technologies” in a handbook are rarely sufficient, and best‑practice agentic workflow guidance emphasises early stakeholder communication.

Where consent is appropriate, it must be informed and granular. Staff should know what categories of data will be used (for example, emails, chat logs, performance data), for which purposes (decision support, training internal models, monitoring trends), how long it will be retained, and whether any third‑party provider can re‑use it to improve their products. Many deployments will require separate consent forms or addenda to employment agreements, written in plain language.

Even when the legal basis is not consent—for instance, where processing is necessary for managing the employment relationship—transparency remains crucial. That means explanation packs, FAQ documents, and internal briefings that spell out what the assistant can and cannot access, which outputs may be logged, and how people can challenge or correct information about them. Without this, you risk both compliance breaches and a cultural backlash, where employees feel monitored rather than supported.

For agentic systems that continually learn from user interactions, you should also clarify whether those interactions will train models beyond the immediate task, and whether any de‑identification techniques are applied. Being upfront about these details—and offering opt‑outs where feasible—reduces regulatory and reputational exposure, particularly when combined with custom, tightly‑scoped automation that limits unnecessary data sharing.

3. Data security and governance controls for AI systems

Because agentic systems often move data between tools—email, HR platforms, ticketing systems—they can become the most attractive entry point for attackers and an efficient way to leak confidential information if left unmanaged, a risk highlighted in agentic AI security and threat models.

Baseline technical controls are familiar: encrypted communication channels, hardened and monitored cloud environments, and multi‑factor authentication on administrative and user accounts. With workplace AI you must apply these controls consistently across internal data sources, integration layers, third‑party AI providers and any sub‑processors. A single weak link exposes the whole chain.

Strong governance defines which data can be fed to AI systems at all, under data minimisation and purpose limitation principles. It sets explicit restrictions around particularly sensitive data—health information, disciplinary records, whistleblower reports—and may ban such data from AI inputs unless there is a documented need and robust safeguards. Access control needs similar rigour: which roles can see prompts and outputs that may contain sensitive staff information, and how those accesses are logged, audited and revoked.

Governance policies should also address retention and deletion. AI tools often cache inputs and outputs for quality or debugging. If you do not know how long these artefacts live, where they reside, and who can access them, you cannot credibly claim control. Clear data lifecycle rules—covering ingestion, transformation, storage, training, and deletion—are non‑negotiable for organisations that want to scale AI while satisfying regulators, boards, and security teams, and should be reflected contractually in your AI terms and conditions.

4. Bias, discrimination and fairness in AI-driven work decisions

When AI touches livelihoods—hiring, promotion, rostering, performance ratings—the risk is deeply human. Bias can creep in through skewed training data, poorly chosen proxies, or the way prompts ask the system to summarise or “rank” employees. Once embedded, that bias can quietly scale across thousands of decisions, a pattern that agentic AI case studies warn about in high‑stakes domains.

Under Australian discrimination and equal opportunity laws, your organisation can be held responsible for unfair outcomes whether they arise from a manager’s judgment or from an AI system used in your decision‑making. If an AI‑assisted decision systematically disadvantages people on the basis of protected attributes such as sex, race, disability, age or family responsibilities, your organisation may still be liable. Legal analysis by ABLA makes it clear that employers remain responsible for recruitment decisions even when a third‑party vendor supplies the AI tool, and that discriminatory intent is not required—if an algorithm disproportionately excludes a protected group, it can still amount to unlawful discrimination. The Australian Human Rights Commission similarly warns that algorithmic bias can lead to unlawful discrimination based on protected attributes like race, age, sex or disability. Research from Melbourne Law School notes that while Australian equality law is still catching up to the realities of algorithmic decision‑making, legal responsibility for discriminatory outcomes generally rests with the user of the technology, such as an employer. Studies on AI in recruitment further caution that both vendors and employers can face legal exposure for discrimination caused by these systems. Consistent with this, the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s guidance on automated decision‑making stresses accountability: a person with ultimate responsibility for a decision must be clearly nominated, even when the process is heavily or fully automated. You also face risks under workplace health and safety laws if psychological harm results from opaque, seemingly arbitrary digital judgments. If an AI‑assisted decision systematically disadvantages people on the basis of protected attributes such as sex, race, disability, age or family responsibilities, your organisation is liable.

Reducing these risks starts before deployment. Identify where AI is influencing employment‑related decisions and run structured bias assessments. That might involve testing outputs across synthetic profiles that vary only by protected attributes, checking error rates for different groups, or reviewing which variables the system relies on most. Where disparities show up, you must decide whether to adjust the data, constrain features, add human checks, or avoid that application altogether.

Day‑to‑day practice matters. Staff need to know that AI outputs are suggestions, not verdicts, and must be weighed against other evidence and professional judgment. Clear escalation channels are vital so employees can challenge or seek explanations for decisions influenced by AI, and so problematic patterns are caught early rather than after a group complaint or regulatory investigation, supported by professional AI governance services where appropriate.

5. Vendor risk, data use clauses and biometric exposure

Most organisations will not build every AI component in‑house. They will buy tools, subscribe to platforms, and connect APIs. That reality makes vendor due diligence and contractual control over data use one of your most powerful governance levers, and one that is often overlooked despite repeated warnings in agentic AI risk analyses about third‑party exposure.

Many AI vendors rely on broad contract language that allows them to use customer data, including employee data, to improve their models, train new features, or create derivative products. Unless you negotiate those terms, staff emails, performance notes, or call recordings could end up contributing to a global model that benefits other customers. At a minimum, insist on clarity about whether your data is used for training beyond your instance, how it is de‑identified (if at all), and what happens to it at contract end.

Biometric data lifts the stakes. Internationally, laws like Illinois’s Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA) have already driven multi‑million‑dollar class‑action settlements when organisations fell short on requirements like informed consent, clear retention schedules, or timely deletion of biometric data. Even if you operate mainly in Australia, these cases are a signal: regulators are paying close attention to biometric AI, and local frameworks are likely to tighten as lawmakers look to heavyweight regimes like BIPA and the GDPR for inspiration. Even if you operate mainly in Australia, these cases warn that regulators are paying close attention to biometric AI and local frameworks are likely to tighten.

When evaluating vendors, map exactly which biometric identifiers they collect, where that data is stored (including overseas locations), who they share it with, and how long they keep it. Contracts should lock in strict consent, disclosure, and retention requirements, with meaningful audit rights and clear remedies for non‑compliance. In practice, that often means working with legal, procurement, and security teams before a tool reaches a pilot—and saying no to vendors who cannot meet your bar, favouring providers with transparent security and governance practices.

6. Audits, monitoring and human accountability

Structured audits and ongoing monitoring are essential. Before deployment, perform a thorough assessment of each AI tool’s data flows: what systems it connects to, what categories of data it can access, where that data is stored, and how long logs and outputs are retained, using patterns from reliable AI workflow engineering to ensure observability and traceability.

A robust pre‑deployment audit also examines whether your data is used to train models that serve other customers, whether any secondary uses are planned (for example, product analytics or research), and how those uses align with your own privacy notices and contractual obligations. The outcome should be a concrete mitigation plan: configuration changes, access limits, additional training, or in some cases a decision that a particular use case is out of bounds.

Once a system is live, you need periodic audits—technical, legal and ethical—to check that the tool is still operating within its intended scope, that drift in the underlying models has not introduced new issues, and that human users are not stretching it into unapproved uses. Logs must be configured from the outset to capture enough information (while still respecting privacy) to trace how key decisions were made.

Accountability must rest with identifiable humans, not abstract committees. Each AI deployment should have a named business owner, a technical owner, and a governance contact who are jointly responsible for its behaviour and lifecycle. That trio should regularly review incidents, staff feedback, and audit findings, and they should have the authority—and expectation—to pause or modify the system where risks outweigh benefits, especially as you scale to multiple assistants orchestrated through different model tiers and routing strategies.

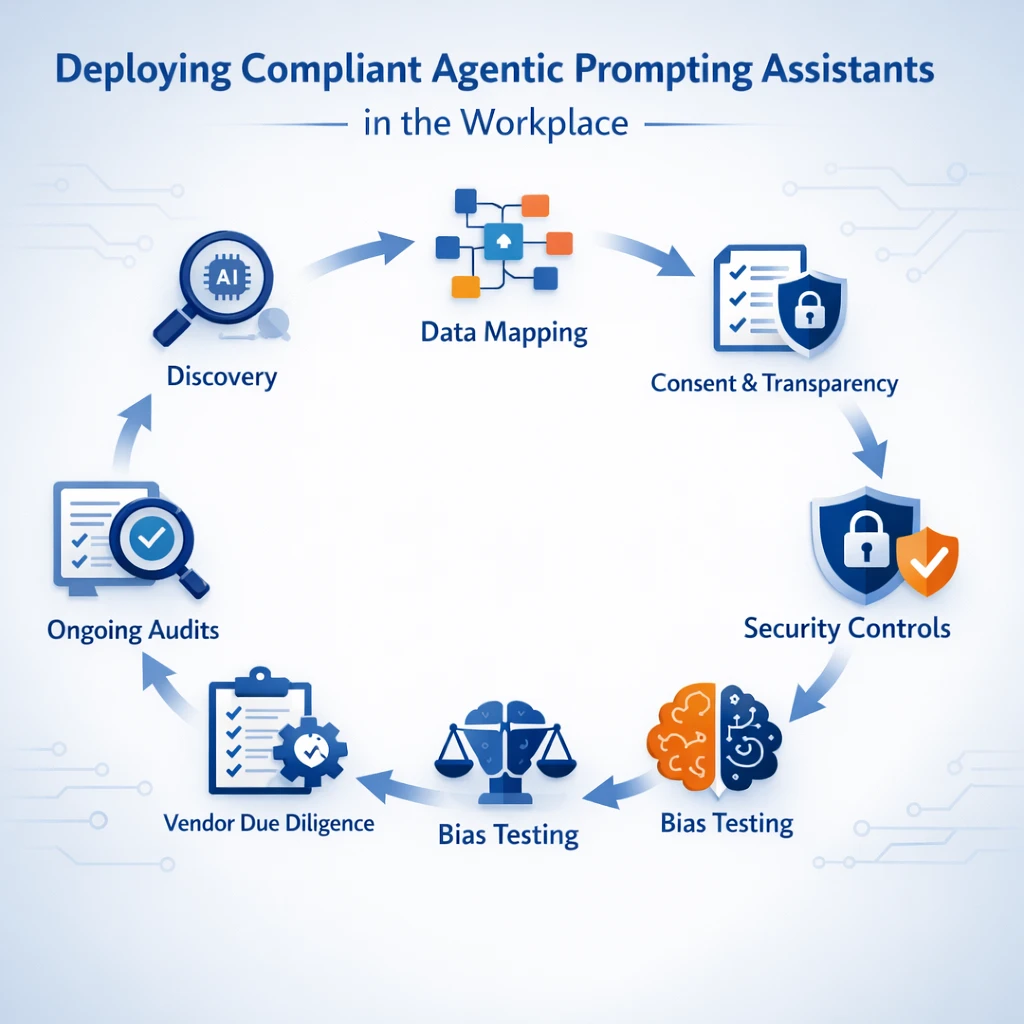

7. Practical framework to deploy compliant agentic assistants

Think in terms of a simple but rigorous lifecycle: define, assess, design, deploy, and review. Each stage has distinct actions for security, privacy, and compliance, and you can start small before expanding across your organisation, following playbooks similar to no‑code agentic workflow frameworks while tailoring them to Australian legal requirements.

In the define phase, specify the business problem, intended users, and decision impact. Are you assisting staff with drafting emails, or influencing who gets hired? That distinction dictates how intense your controls must be. Document what data the system will need and which systems it will touch.

During assess, run a structured risk and compliance review. Map applicable Australian laws and internal policies, identify whether any special categories of data (such as health or biometric information) are involved, and decide whether consent or enhanced transparency steps are required. This is also where you perform vendor due diligence if you use external platforms, scrutinising data use clauses, security posture, and any international data transfers.

The design phase focuses on building in safeguards. Configure access controls, data minimisation rules, and red‑lines around which data the system cannot see. For high‑impact use cases, incorporate explicit human‑in‑the‑loop stages, bias checks, and explainability mechanisms (even if they are procedural rather than technical). Draft internal guidance so users understand both the power and the limits of the tool, and align technical choices with your model performance and cost trade‑offs.

In deploy, start with limited pilots, clear communication to affected staff, and tight monitoring. Capture logs, feedback, and edge cases. Use those signals to refine prompts, permissions, and user training before any wide roll‑out. Make it easy for employees to raise concerns or report unexpected behaviour, and respond visibly when they do so, leveraging secure Australian AI assistants that support granular controls and local data residency.

The review phase should be continuous. Schedule periodic audits, revisit risk assessments when models or use cases change, and track whether the assistant is drifting into areas you never originally approved. As Australian and global regulations evolve, feed those changes into your framework so it stays aligned rather than forcing rushed retrofits later on, using resources like your AI implementation policy and knowledge base to keep documentation current.

Conclusion and next steps

Agentic prompting assistants are a new layer in the social and legal fabric of work. In Australia’s shifting regulatory landscape, organisations that treat security, privacy, and fairness as design inputs—not compliance chores to clean up later—will be best placed, mirroring broader guidance on responsible agentic workflows.

If you start with clear legal foundations, earn employee trust through honest transparency, lock down your data flows, interrogate your vendors, and keep humans clearly accountable, you can harness AI’s benefits without sleepwalking into avoidable risk. The framework in this article is designed to be used—take one live or planned use case and walk it through the stages this month, ideally supported by specialist AI compliance and deployment services where internal capacity is limited.

To round out your strategy, you may also want to revisit Parts 1 and 2 of this series, which explore the conceptual and workflow dimensions of these systems. Together, the three parts will help your organisation move from scattered experiments to a mature, compliant ecosystem of AI tools that genuinely support people at work, and position you to expand into more advanced automation and agentic capabilities over time.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an agentic prompting assistant in the workplace?

An agentic prompting assistant is an AI system that can plan tasks, call tools or APIs, and act across multiple platforms with minimal human intervention. In workplaces, they may draft performance feedback, route customer queries, or flag at‑risk employees by analysing large volumes of HR or operational data. Unlike simple chatbots, they can take multi‑step actions based on goals, not just answer single questions.

Are agentic AI assistants legal to use in Australian workplaces?

Yes, agentic AI assistants can be used in Australian workplaces, but they must comply with existing laws such as the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth), Fair Work laws, anti‑discrimination legislation and relevant workplace surveillance laws in each state or territory. Employers must ensure there is a lawful basis for collecting and processing employee data, provide appropriate notice, and avoid unlawful discrimination or unfair treatment based on AI‑generated insights. Regulators increasingly expect clear governance, human oversight, and the ability to explain AI‑influenced decisions.

What do employers need to tell employees before using AI assistants on their data?

Employers should clearly inform employees what AI systems are being used, what data will be processed, for what purposes, and who the information may be shared with. This typically requires updated privacy notices, workplace policies, and in some jurisdictions, surveillance notifications that are provided before monitoring begins. Transparency should cover automated profiling or risk scoring, and employees should know how to raise concerns or request review of AI‑influenced decisions.

Do I need employee consent to deploy agentic AI tools in HR and performance management?

In Australia, employers usually rely on legitimate business needs and legal obligations rather than consent for core HR processing, but consent may still be required or advisable for certain high‑risk uses, sensitive information, or biometric data. Even where consent isn’t strictly required, regulators expect that employees receive clear notice, have reasonable expectations about monitoring, and that intrusive or novel uses are carefully justified. Legal advice is recommended when AI tools profile employees, use biometric identifiers, or are linked to adverse employment actions.

How can we make sure our AI assistant is secure and complies with Australian privacy law?

You should implement strong access controls, encryption, role‑based permissions, logging, and retention limits around all data sent to and from the AI assistant. Conduct a privacy impact assessment (PIA), map all data flows (including overseas processing), and ensure contracts with vendors include Australian Privacy Principle (APP)–aligned clauses. Regular audits, incident response plans, and staff training on appropriate data input are also critical to maintaining compliance.

How do we prevent bias and discrimination when using AI for performance or hiring decisions?

Start by limiting the AI assistant to support and augment human decision‑making, not replace it for high‑stakes employment outcomes. Use diverse, representative training data where possible, test models for disparate impact across protected attributes, and document what factors the system can and cannot consider. Establish review processes where humans can override AI recommendations, and ensure adverse decisions are based on explainable, lawful criteria that can be defended under anti‑discrimination and Fair Work laws.

What should we include in vendor contracts for workplace AI and agentic assistants?

Vendor contracts should clearly define data ownership, permitted uses of your data, data retention and deletion, security standards, locations of data storage and processing, and rights to audit or obtain security reports. You should also address model training on your data, sub‑processors, breach notification timeframes, and compliance with Australian Privacy Principles. For tools that may process biometric or highly sensitive employee information, require explicit prohibitions on secondary use and strong technical safeguards.

Are there special risks with biometric or voice data in AI assistants?

Yes, biometric identifiers such as facial images, fingerprints, or voiceprints are considered highly sensitive and can trigger stricter legal and ethical requirements. If an AI assistant processes recordings, video, or authentication data, you need clear justification, explicit notices (and often consent), and strong security controls. Misuse or breach of biometric data can expose organisations to significant regulatory, reputational, and litigation risk.

How should we audit and monitor agentic prompting assistants once deployed?

Set up regular audits that review access logs, decision outputs, error rates, bias indicators, and compliance with your AI and privacy policies. Establish human accountability by assigning named owners for each AI use case, and create an escalation path when the system behaves unexpectedly or makes a high‑impact recommendation. Periodically test the assistant with real‑world scenarios, document changes to configurations or prompts, and keep an audit trail that can be shown to regulators or courts if needed.

What practical steps can an Australian company take to roll out compliant agentic assistants?

Begin with a use‑case inventory, risk assessment, and a pilot in a lower‑risk area, then build or refine policies for AI, privacy, acceptable use, and incident management. Put technical guardrails in place (like data redaction, scoped tools, and environment segregation), train staff on safe prompting, and engage legal or governance experts to review high‑impact use cases. LYFE AI can support organisations through this process by designing secure architectures, configuring agentic assistants with compliance in mind, and helping teams operationalise governance frameworks.